Brief Border Wars. The Football War: the Battle of Nacaome

Scenario: The Football War

Salvadoran: Laura Beltrami

Honduran: Alex Isabelle

The conflict that goes by the elusive name of "football war" was one of the shortest war in history: it lasted a total of four days, yet this was enough to leave about six thousand dead on the battlefield, more than half of them being civilians.

In spite of the name, therefore, it was not a simple brawl between the hooligans of El Salvador and Honduras, but the explosion of tensions accumulated over several years and opportunistically fueled by both governments. On the one hand, the xenophobic policy of the Honduran dictator Oswaldo López Arellano had directed popular anger in the direction of the more or less irregular immigrants who had moved to Honduras due to the overpopulation and the huge employment rate in El Salvador. On the other hand, the latter country was facing a series of domestic political problems: the society was fragmented and unhappy and would have reacted positively to a war with a nationalistic flavor against its hated neighbor.

|

| The starting situation. |

The spark that detonated the bomb was the 1970 World Cup, which was held in Mexico. The teams met twice to determine who would have access to the playoffs; both games, played first in Tegucigalpa and then in San Salvador, were marked by an extremely violent participation of local football fans. A third play-off game was needed, which was played in Mexico, in the presence of both group of supporters and five thousand policemen who could not keep them apart when, in the extra time, El Salvador won 3 to 2. The scuffles were transformed soon in a real urban warfare. The nationalist government of Honduras decided not to miss anything and immediately broke off trade agreements and diplomatic relations with El Salvador. Two weeks later, the latter's army crossed the border.

Here our simulation begins. It was our first game of Brief Border Wars and we had initially underestimated the importance of roads, which caused us to make a number of significant mistakes.

Half of El Salvador's army was positioned in an area with no communication routes, a very inconvenient place to commence an invasion. The other half, which remained nearby, instead immediately crossed the border, reaching the city of El Amatillo, defended by a single infantry unit that was immediately eliminated. Unaware of the invasion, Honduras had positioned its few border troops at the customs borders between the two countries, while a third unit, a group of military police, was stationed in the mountains that marked the border.

|

| The Salvadoran administation observes disenchantment the war developments. |

The main contingent of Honduran troops, coming from the hinterland, headed quickly towards the vanguard of El Salvador, which in the meantime was preparing to penetrate towards the city of Nacaome, more populous and therefore more useful for the demonstration of strength that El Salvador wanted to put in place.

While in the remaining points of the border the sparse Honduran troops encroached on the territories of El Salvador, aspiring to take control of the communication routes, the bulk of the two armies instead started an intense guerrilla warfare in the streets of Nacaome, which saw the use of the obsolete air forces by both countries. These also made use of civilian aircrafts, some C-47s converted for military use.

By the end of the first day of fighting, therefore, Nacaome had become a hell of bullets and bombs. The second day saw the Honduran counter-offensive progressively disperse, even if at the cost of many losses, the Salvadoran vanguard, which still managed to maintain partial control of the city.

At the dawn of the third day came the call for a ceasefire from the United States and the Organization of American States. That organization was taken seriously by Honduras, which decided to stop its own counter-offensive, hoping that El Salvador's troops did the same. On the contrary, the government of El Salvador ordered to proceed with the fightings, pointing to the fact that Honduras had become more vulnerable. Other Salvadoran troops trespassed, heading from the mountains towards El Amatillo and then to Nacaome, resuming the clashes against the now disorganized Honduran troops.

|

| The bombing of El Salvador airport, the airport of San Salvador, capital of El Salvador. |

The central administration of the Honduran army immediately plunged into chaos and only a consistent test of discipline was able to restore the functionality of the aeronautics: having to patch up its almost total disorganization, the Fuerza Aérea Hondureña was sent to bomb in mass the El Salvador civil-military airport. This caught Salvadoran forces off guard, with several planes put out of action. For the rest of the day, therefore, the attacking army had to conduct its operations without air support, which mitigated their impact and prevented them from finally taking control of the now devastated Nacaome.

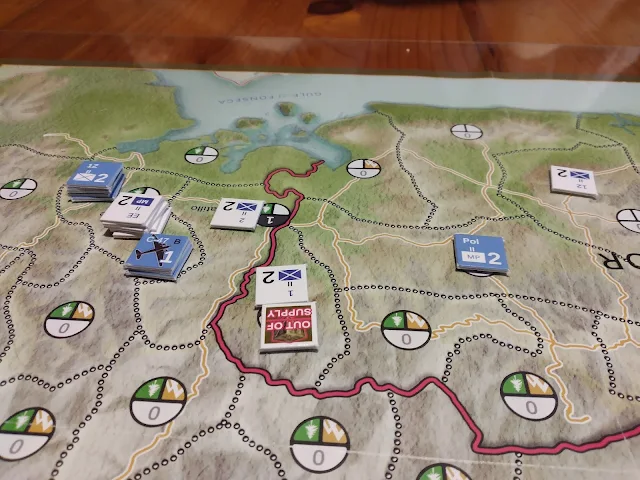

During the night, meanwhile, the Honduran military police reached the hinterland of El Salvador, taking control of an important road artery. This move, completely neglected by the Salvadoran army, left troops in El Amarillo and Nacaome without supplies, which once again failed to deliver the coup de grace to the Honduran army.

|

| The occupation of Ocotepeque and La Labor. Notice that all the troops here are out of supply. |

On the fourth day the clash continued more ferocious than ever: new troops arrived from San Salvador, attacking the other customs access with Honduras, near Ocotepeque, which was immediately occupied. The haggard border guard conducted a disorganized retreat, which left the El Salvador troops free to soon take control of the nearby city of La Labor as well; the attackers continued occupying, within a few hours, the completely defenseless Santa Rosa de Copán.

The conflict was beginning to fade. On the evening of the fourth day, the border troops who had initially defended Ocotepeque regrouped and returned to the city, loosening the Salvadorian grip on it; at the same time, a Honduran contingent moved south and reached El Amatillo. Because of this, the clashes reignited even on the very first front.

At the dawn of the fifth and final day, international politics took their course: the Organization of American States threatened with heavy sanctions El Salvador, condemned as an aggressor state. The threat of further sanctions also on Honduras, in the event that the anti-Salvadoran propaganda did not end, produced the desired effect. The two armies ended the fighting and returned orderly to their ranks.

The aim of this war for El Salvador was to make a show of force, which however did not have the desired effect: only two cities (La Labor and Santa Rosa de Copán) fell completely under the control of the attacking troops; all the others remained disputed by the two sides until the end. Ultimately, the nationalist campaign of which this war was to be the centerpiece was unsuccessful and this resulted in a minor political victory for Honduras.

Do you want to read other stories? Click here for the full list.

Great replay. We have featured your article in ConsimWorld Brief, Issue 4. Keep up the great work!

ReplyDeletehttps://consimworld.curated.co/issues/4

Ehy, thank you very much :D

DeleteI noticed a peak of visitors coming from consimworld and in fact I was wondering how did we end up there. Very nice portal, I'll keep an eye on it ;)

Besides, we just published a new report about an other BBW scenario, you might find that one interesting as well :)