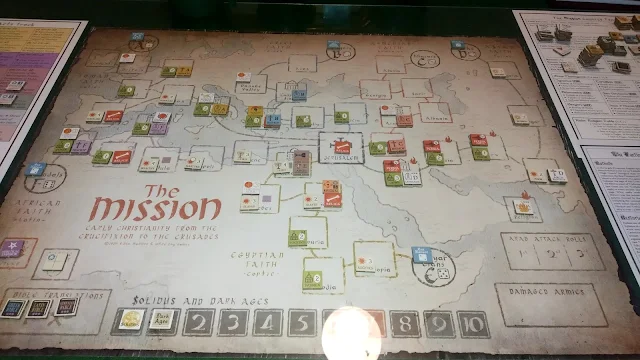

The Mission. On the Copts and their natural tendency towards heresy (part 3 of 6)

Three hundred years have passed since the crucifixion of the Nazarene. The Mission of Christianity is doing badly but not TOO badly, dealing with Ethenian popes and Anatolian pilgrims who upset the doctrine of Coptic Christianity, with bishops in love with pagan women and great theologians who try to straighten out a Christian tradition in which everyone feels they can have their say. But now everything changes! And everything will go swimmingly, right? Because thus begins the...

Third era. Age of Constantine (301 AD - 450 AD)

With the coming of the first Christian Emperor it seems that the game is destined to become easier. This is very important news: Christianity is no longer the religion of slaves but a trendy doctrine, embraced by the highest political office in the Eurasian area. Bishops and archbishops rub their hands at the thought of the great things that can be done with access to the means of the Roman Empire. Just as the Parthian Empire ultimately mostly abandoned Zoroastrianism in favor of Christianity, soon the entirety of the Romans will also be able to call themselves Christian; it's just a matter of waiting.

And then, suddenly, the news.

Emperor Constantine is HERETIC.

I consult the map to try to understand this absurdity, and the fact is quickly explained: Rome is still dominated by the Ebionites! It is them, with their customs suspended between the old Jewish traditions and the novelties of Christian rites, who have produced the Caesar, not my pious bishops!

Bitterly, I watch my Christian world go haywire. The philosophical debate on the absurd theories advocated by Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantinus takes away from me control over the Christian offices currently active within the Roman borders. The Emperor himself convenes a pair of ecumenical councils, the first since the beginning of the Mission, the council of Arles and then that of Nicaea, to discuss (and from what a pulpit!) the most popular heresies at the moment and how to treat them. I don't know what they say exactly, but the result is that the Greek and Asian branches distance themselves from the Roman one: the latter, dominated by the heresy of Constantine, materializes in the Catholic Church, while the other two, rather unhappy about the Ebionite drift which the entire Latin lineage risks to encounter, embraces more orthodox ideas, thus giving birth to the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox Church of Asia, that of the Persians, in particular considers the possibility of a schism, but the more conciliatory attitude of the Greeks fortunately lead them to desist.

|

| The coming of the first heretical Emperor, the antichrist Constantine, is accompanied by the transcription of the New Testament into Greek. |

In short, the thirty years of Constantine are a confused theological squabble that leads, in geographical terms, to nothing but divisions. The religious discussion even starts to touch morbid financial matters: people interested in purchasing the relics of the saints appear. The amount offered is modest but there are those who are seriously thinking about selling the bones of the apostles in the near future. The only positive fact is that the Greeks, finally realizing how much the Torah is still capable of spreading Jewish customs, decide to provide an alternative to them, codifying the Christian myths in a gospel. Finally the New Testament appears, which at this point is written solely in Greek, though. We will have to translate it if we want to do something with it in the rest of the world.

What puts an end to the religious crises is the death of the serpent in the womb, Constantine, who also hands over to posterity an Empire no less fragmented than the Christian world, which if you think about it, frames him in all respects as a true antichrist, who first divides the people of God and then does the same with the kingdoms of the earth. A very different image from that of the historical Constantine... but whatever: political matters are none of our business, and indeed the religious world, with the passing of the Emperor, can finally breathe. The totality of the faithfuls' coffers is therefore invested for a noble purpose: the elimination of the Gnostics from Alexandria, about whose heresy none of the various expressions of post-Constantinian Christianity has anything to laugh about, also because the Copts have not paid a penny into the Church's common fund for forty years and this is starting to get unnerving. At the end of the day the meeting with the new Coptic Pope, Athanasius of Alexandria, manages to produce some fruit. The sympathetic Athanasius not only abandons Gnosticism, in fact, but makes amends and takes steps to eliminate the entire Gnostic sect himself, once and for all, from the map. They tell him that this may be enough, but he wants to make amends, also because it is good that we have made peace, but there are those who, not wrongly, accuse him and his community of having siphoned so much of that money that by investing it well the Bible, by now, could even have been translated even into sabir language. Then Athanasius leaves on a pilgrimage: he first goes to Antioch, where he meets the Ebionites, presents them with the new version of the Testament, and disperses them. Then he proceeds towards Armenia and does the same thing. Finally he heads towards the Caucasus region, facing what by all accounts is a certain martyrdom, expecting to meet the lone Mithraists of Alania. And instead after a few years he returns home claiming to have brought the light of reason even to those distant people. He returns to Alexandria to fulfill his papal duties; upon his death he will be canonized and venerated as a saint.

|

| Athanasius is not joking. |

The example of Athanasius does not go unnoticed in the eyes of Emperor Constantius II, the only survivor of the massacre that in the meantime has been the Constantinian succession. Constantius II is finally truly a Christian Emperor: the terrible example of his father Constantine tells him that heretics are a problem that the more clearly it is resolved, the better. Having received news that there are still two heretical sects within the borders of the Roman Empire, namely the Marcionites in Spain and the last Ebionites in Rome, he mobilizes the scholae palatinae, the updated version of the praetorian guard, giving them the task of identify these groups and neutralize them. Which is done within a few years with torture and summary justice. This massacre of human rights moves the marker of the dark ages two steps in the direction of barbarism. The history of humanity shudders; that of Christianity, on the other hand, is grateful, because finally after three hundred years there are no longer heretics on the map, and in particular there is no longer anyone who maintains that the Torah is the only true canonical text. We decide to toast. No, not a toast, let's have a party. Indeed, let's have something bigger than a party. Let's discuss this in a council!

From comedy to tragedy is a moment: the First Council of Constantinople arrives.

In what, historically, was the second of the great ecumenical councils dedicated to the Arian heresy in the world, it is not clear what is being discussed here, given that the Arians have not yet shown themselves and all the other heresies have been completely eradicated from the entire Christian world. The fact is that there is always a way to argue: one word leads to another and suddenly someone raises the issue of the Copts. Copts who, although on paper they have abandoned heresy, nevertheless it turns out that they have some theory of their own regarding the divine nature of Christ, on which they do not accept any compromise. To general amazement, the Copts announce that they are calling their branch the Coptic Miaphysite Church, in opposition to the Catholic and Orthodox ones. Astonishment, insults, slaps. At the end of the council the Copts use the word that no one had previously had the courage to pronounce: "schism". They go home slamming the door and specifying that they will go back to not paying their membership fee contributions to the common fund. Catholics and Orthodox curse them, sending the bones of Athanasius I to hell and banning his cult in their lands. Then they close the council before doing any more damage.

|

| The Copts do a schism, the Sabellians take Cyrenaica. Alexandria's area is a swamp where dogmas go to die. |

Since the Copts do what they want, even the very small community in the nearby region of Cyrenaica feels that the times in which each community had its own variant of Christianity are back. Thus is born the Sabellian heresy, a twisted and almost alchemical vision of a God who is at the same time, but in temporal succession, Father, Son and Holy Spirit... the new Emperor Valentinian I, the first emperor after the problematic lineage of antichrist Constantine, is an admirer of the method of Constantius II, and as soon as he hears about the Sabellians he sends the army there to eradicate the cult in the bud. The repression is so effective that nothing will ever be written about the Sabellians again, not even in university books. However, the dark ages counter moves a little further to the right.

|

| With the conversion of Gaul and Belgium, Europe is taking on a pleasant green hue. |

Meanwhile, the Catholics accept the fact that there will never be a way to find a solution with the Copts, and they concentrate on their own area of influence, which is still largely pagan. The bishop of Spain, a position which still consists of the care of the mortal remains of the Apostle Peter, receives the order to get busy. He moves to Gaul, converts the poor communities, and then moves to Belgium, where he meets women, as has already happened to some of his predecessors elsewhere in the world. He returns to Gaul for some time, managing to deprive himself of the desire for carnal love, and then returns, now a chaste man, to the women of Belgium and converts most of them to Christianity.

The results obtained are good, which allows the Great Theologian of those years, John Chrysostom, archbishop of Constantinople, to find the time to resume the teaching of the old Origen of Alexandria: he begins to write an enormous amount of homilies, pamphlets, letters, with the aim of bringing order to Christian doctrine around the world. He particularly focuses on spreading awareness that the imperial repression of heresies is good and right, and this calms the minds regarding the methodical repression carried out by Constantius II and Valentinian I. His work lowers the dark ages counter by 1.

So the military repression of heresies becomes part of the Christian doctrine itself, at this point. Twenty years later, in fact, the situation arises again: a group of Manichaean heretics is born on the borders of the Roman Empire in Africa, in Mauretania Tingitana. These followers of the Babylonian false prophet Mani, who claims to be the only true disciple of Christ, are reached by the scholae palatinae of Emperor Theodosius and exterminated. Augustine of Hippo, who was historically involved in the Manichaean heresy, in this case takes up the work of John Chrysostom, continuing the activity of updating the Christian canon after his death. The advent of the dark ages therefore remains under control. Part of his activity also consists of translating the Bible used by the Greeks into Latin. Many copies of this Latin Bible are sent to Rome, reaching the still Jewish communities in that city. The new version of the Testament is found convincing, and so for the second time the local Jews convert en masse to Christianity.

|

| North Africa in the aftermath of the birth of the African Miaphysite Church. |

As the damage caused by the antichrist Constantine is overcome, the third era of the Mission is coming to an end. To take stock of the situation, a council is convened, to discuss plans for the future, the Council of Ephesus. Agenda: the Copts, or miaphysites if you prefer. What to do with them? Are they heretics or just pricks? The representatives of the North African branch timidly raise their hands, saying that all in all they have thought about it: this story of the single nature of God, i.e. the foundational core of the theories of the miaphysites, in the end seems to make sense. Indeed, that theory has now spread independently throughout the entire branch starting from Cyrenaica, close to the schismatic Alexandria. Since things have developed in this way, the Patriarch of Carthage, who calls himself "Servant in Charge", would like to take the opportunity to announce the foundation of the African Miaphysite Church. Astonishment, insults, slaps, then the Carthaginians explain themselves better: miaphysites yes, but schismatics no. At the news that they will continue to pay their share of the budget, spirits suddenly calm down, and indeed, fingers are crossed that the Africans can convince their Coptic friends to return to the ranks. For once the council ends without doors being slammed, and after a few handshakes everyone goes home with a lighter heart.

|

| Manichaeism flourishes along the coasts of the Red Sea. |

The only one who has confused ideas is the Emperor of the Romans, Honorius, who is reached by Manichaean ideas, which in the meantime also flourished in the region of Nobadia, along the shores of the Red Sea, confirming that in those parts heresies grow strong. He becomes convinced that this is real Christianity, and alone gives rise to an intense religious debate, completely unrelated to what was just discussed in Ephesus. Upon their return to their respective homelands, the various patriarchs find a Christian world at the mercy of the storm. The Coptic Archbishop of Alexandria himself, who had not participated in the Council due to the schism of his church, is involved in these diatribes and is unable to go to Nobadia to speak with the Manichaeans, who in that region become so influential that they convince almost all the local slaves to abandon Coptic Christianity. It is decided to wait for better times to come: the only one who is busy is Leo the Great, alias Pope Leo I, the Pope of Rome, who spends a lot of energy meeting Honorius and trying to reconcile souls. Honorius dies as a heretic, but the further disintegration of the Kingdom of God is averted. History thanks us, and the dark ages marker moves back to a reassuring 1, while, taking advantage of the dead time, the Bible is also translated into Armenian by the faithful of the neglected Antioch.

|

| Bibles are multiplying. |

With Honorius' passing to a better life, the situation seems chaotic but manageable. The Bible is beginning to circulate in a reasonable number of copies and languages, and the Christian doctrine is now consolidated, despite some internal divisions which, however, have resulted only in the schism of the Copts.

It seems that the situation, although it started off on the wrong foot, can evolve positively. Even the schism could be mended, and we are starting to think about how this could be done. No one expects, however, the abyss towards which history is proceeding in great strides.

See you in a week with part 4, in which Rome... falls!

Do you want to read other stories? Click here for the full list.

|

| Dark times are looming on the horizon. |

Comments

Post a Comment