The Mission. On the Copts and their natural tendency towards heresy (part 1 of 6)

Christian: Alex Isabelle (I'm laughing already)

Prologue. The crucifixion

We travel back two thousand years, reaching one of those rare moments in which history and legend merge to become myth.

We are in Jerusalem. The year is 31. Or 30. Or 33. Scholars do not agree, but in 31 we know that there was an earthquake that seems to have had effects attributable to some things described in the Gospel of Matthew. As a scientist I choose to follow the indications of geologists and therefore, for me, we are in 31.

The crucifixion of Christ takes place, an act that must seem decisive to those who are responsible for putting the unfortunate person to death, i.e. the Roman occupying forces. These people basically find their hands tied: the words of the new messiah are generating an ungovernable mayhem and the matter must be closed once and for all.

The opposite effect is instead obtained: faced with the torture on Calvary, the cult built around Christ emerges strengthened, thanks to the apparently inexplicable disappearance of his body shortly after his burial. Something that I personally explain with the stealing of the body, something also suggested by the Gospel of Matthew itself... but anyway. The faithful choose to justify this with the resurrection of the messiah and, whether one believes it or not, this helps to definitively root what we today call Christianity around the area of Jerusalem. The supposed resurrection gives strength to the words of the apostles, who at this point intend to move towards the various corners of the earth (six, according to this game) to bring the word of God among the unbelievers and create his kingdom, in view of his second coming.

I have the unusual task of spreading its belief on the game map, through about a millennium of history.

First era. The apostolic age (30 AD - 90 AD)

At the beginning of the game, the scenario on which future Christianity will extend is populated by an infinite number of pagan cults. Among them, that of Isis stands out, now destined to decline, and which nevertheless survives in Carthage and in the Nile region on which the future kingdom of Alodia will rise. Mithraism is also solid: a religion of mixed fortunes and now doing quite well in Constantinople and the Caucasus area.

The Roman Empire is already in a recession by now, but does not suffer from external threats: its main army is parked in Greece. Rome is, it goes without saying, still pagan.

.jpeg) |

| The barbarism to which Christians are subjected in Rome convince the local Jewish communities of the validity of their ideas. |

However, it is precisely the Lex Romana that interferes first, and positively, with the intentions of the apostles. The feverish diffusion of the word of God in fact independently makes its way to the Eternal City through a long word of mouth. Here the Emperor Tiberius decides to continue the work of demolition of the Christian cult begun in Palestine by feeding several of its most audacious supporters to the lions. Which, from a gaming perspective, is a good thing, because this gives more credibility to the mission of the apostles: the Jewish communities based in Rome, in fact, thanks to the sad spectacles of Tiberius begin to seriously discuss the ideas brought forth by the Christian sect, ending to embrace them to a large extent.

At the same time, natural disasters also decide they want to play their game: in the Parthian Empire, the Mesopotamian city of Ctesiphon, one of the most populous metropolises in the world, is devastated by a plague epidemic. The Christians present there attempt a coup, trying to present prayer as an act of purification, but it doesn't work and the Persians prefer to keep their Zoroastrian cults, offering their votes to Zarathustra, or whoever for him, until the plague goes away naturally.

|

| The apostles plan what to do. Around them a world populated by unbelieving Jews. |

The apostles still have to pack their bags, and in the meantime they formulate an action plan. The effort made independently in Ctesiphon by the small community of believers should not be allowed to fall on deaf ears, they agree, and therefore it is decided to try to immediately convert the entire Parthian Empire. James the Just is the first to work in this direction, trying to exploit the contacts of the Jewish families of Jerusalem in order to trace back to some Jewish group in Ctesiphon that might be willing to embrace Christian ideas. However, something goes wrong because, in response, his fellow countrymen poison him. James' unfortunate fate gives the push the other apostles need to set out and abandon Jerusalem before things get bad for them too. They greet each other, and each goes his own way.

.jpeg) |

| The horror... the horror! |

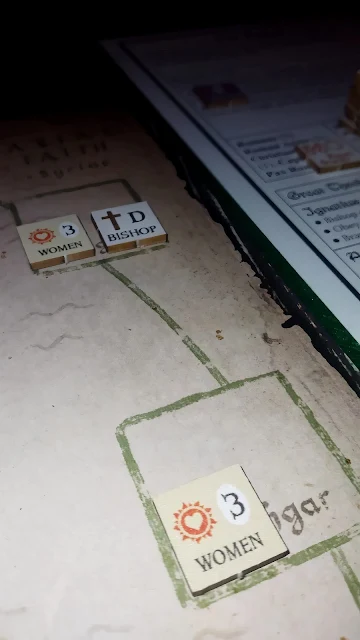

After the failures of the locals and of James, the apostle Thomas is the one who gets the thankless task of trying for the third time to insinuate the Christian belief in Persia. He travels for a long time, looking for a suitable place to plant the seed of Christianity. His words are pearls before swine, at least from his point of view, but in any case he does not give up, and he continues his journey towards the East for years. He travels so long that he goes straight and passes the Parthian Empire, arriving in India, where he meets the poor local populations. Mindful of the Palestinian experience, Thomas attempts an approach towards the latter. He immediately is put to the sword and sacrificed to Kali. A young man whom Thomas had convinced of the Christian belief, and whose name has been lost to history, however takes upon himself the missionary task, traveling north and after a year's journey reaching the city of Kashgar, where he discovers a potential demography interested in Christian doctrine: women. Horrified by love and sex, the once boy, now man and first bishop of Syriac Christianity, returns to his original village in India, where he reflects on what happened for a couple of years. Finally putting aside the hormonal impulses typical of sinners he finally returns to the north. Once in Kashgar he chooses to settle there and stop travelling. So wanted the Mission, he will say, trying to disprove the gossips who want him back in the company of her who led him to sin.

The other apostles do not experience more successful journeys. Starting with Barnabas, who moves to Antioch. Tracked down by the Jews who had already killed James, he too is immediately stabbed and left to bleed out in an alley. Slightly luckier is Mark, who lands in Alexandria, escapes from the Jewish assassins, reaches Thebes, continues along the coast of the Nile and joins a group of slaves. The attempt to convert them is reported to the slavers who, not happy with this, strangle him and feed him to the crocodiles. His fate is similar to that which befalls Judah, who at least has the pride of making the acquaintance of almost all the peoples of North Africa before being hanged by a group of slavers from Numidia. Peter, who chooses to explore modern-day Europe, initially has an easy time, because he lands in a Rome where the Christian community, at this point, is already very strong. He continues until he reaches Spain where he finds a dense community of scholars apparently well disposed to religious debate. However, something gets lost in the translation, because after a not very convincing exchange of knowledge he is neutralized. A fate similar to that of Paul, who upon reaching a community of ascetics in Greece discovers, paying for his mistake with his life, that the latter do not want to be faced with doubts of faith during the course of their, albeit pagan, functions.

.jpeg) |

| The Ebionite sect of Rome is born. At the end of the round that green chit will turn, to signify a return to the heaten (Jewish, in this case) ways. |

A couple of decades after the death of the messiah, therefore, all the apostles have in turn passed away. All of them, however, were able to leave their roles to bishops, together with their relics, already venerated by a small number of faithful.

Another ten years pass and the Jews of Rome, left without a spiritual guide, continue to independently discuss what Christianity really is. The New Testament has not yet been written down and so they turn to the Old for guidance. This recourse to old scriptures transforms the newborn Christian group of Rome into a sect located halfway between Christianity and Judaism that the Christians of Jerusalem call "Ebionites": heretics, done and finished.

|

| The horror never ends! |

With the apostles all dealt with and with the only community of Christians outside Jerusalem that re-embraces the teachings of the old Torah, it would seem that the mission of Christ's faithful has already gone to the dogs. However, after fifteen years of reflection, the bishop of Kashgar decides to set off north again and reach Mongolia, mindful of his youthful years. And ironically, life puts him face to face with the same challenges of the past: the Mongolian women appear to be permeable to Christian teachings, but some of them disturb the man, again, who in desperation returns to Kashgar, where he gives in to his own fallibility and definitively abandons his task, leaving it to someone with a more rigid faith than his. The new bishop then returns to Mongolia, resists the temptation, and proceeds even further north, towards the lands inhabited by the Turkish peoples. Having reached this point, the missionary decides that extending Christianity further than this makes no sense: Thomas had spoken of converting the Parthian Empire, not the peasant villages in the Urals. He therefore declares himself archbishop, reverses the direction of travel and travels to Persia, where he settles until the end of his days with the aim, never realised, of making it a true Christian community.

The beginnings of the Mission are timid, and frankly do not bode well for the developments it will encounter in the years to come. However, Christians have chosen a religion based on pain and penance, so I presume that there are, among missionaries, those who find this uphill walk stimulating. After all, we are only in the first century: the story is still long.

For the moment the main threat to the Christian faith seems to be represented by women, and perhaps by that Ebionite sect in Rome. But, given time, the missionaries will discover that there are very different concerns they will have to face. Like for example the rain of heresies that is foreseen on the horizon, not to mention the "Coptic affair", whose seeds are starting to sprout already.

See you in a week with part 2, in which Christians deal with their first doubts of faith.

Do you want to read other stories? Click here for the full list.

Comments

Post a Comment